Central Auditory Masking

In Audiology the word masking denotes the presence of a sound that interferes with another. Since we live in a world filled with sounds, there is always some masking when we are talking or listening. In some circumstances there is more masking. A good example is a cocktail party: we may be talking to one person and in the background we hear other people talking, music, waiters clashing dishes, and so on.

For audiological tests we use well defined types of noise as masking devices. Most of the masking effects occur in the inner ear, but it can also occur in the central auditory pathways (the route from the inner ear to the brain).

During my third and last year in Saint Louis I spent three weeks at the Research Department of the Central Institute for the Deaf, involved in audiological research. I felt that this would somehow complement my years of training and it was a very pleasant experience.

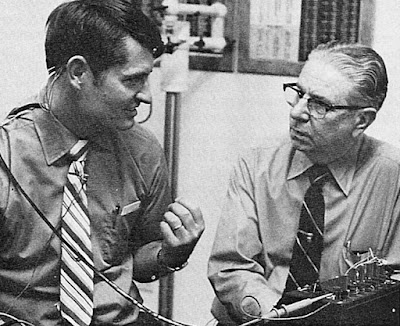

Carl Sherrick, an experimental psychologist, was doing some experiments with pulsed stimuli and invited me to help him. We found that the masking noises provided more masking when they were pulsed simultaneously with the sounds. This was unexpected, and we really did not know why it was happening. We published the observations just before Carl moved to the University of Virginia and I returned to Brazil.

In 1964 I attended the American Academy Meeting, in Chicago, and most of my friends from Saint Louis were also there. Don Eldredge, a CID neurophysiologist, had attended the Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and told me, laughing: “Your ears must be ringing, everybody was talking about the Sherrick and Albernaz paper...”

Several years later, in a Collegium ORLAS Meeting, Dr. Jozef Zwislocki, an eminent audiologist, asked me how, being an otolaryngologist, I became involved in that study. “We now know,” he told me, “that this was the second paper published on central auditory masking. For a while we thought it was the first, but then we found an earlier paper published in England, one month before yours. But your paper was very important and opened a total new field in audiology.”

Sherrick Jr CE, Mangabeira-Albernaz PL. Auditory threshold shifts produced by simultaneously pulsed contralateral stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am. 1961; 33 (10): 1381-5.

For audiological tests we use well defined types of noise as masking devices. Most of the masking effects occur in the inner ear, but it can also occur in the central auditory pathways (the route from the inner ear to the brain).

During my third and last year in Saint Louis I spent three weeks at the Research Department of the Central Institute for the Deaf, involved in audiological research. I felt that this would somehow complement my years of training and it was a very pleasant experience.

Carl Sherrick, an experimental psychologist, was doing some experiments with pulsed stimuli and invited me to help him. We found that the masking noises provided more masking when they were pulsed simultaneously with the sounds. This was unexpected, and we really did not know why it was happening. We published the observations just before Carl moved to the University of Virginia and I returned to Brazil.

In 1964 I attended the American Academy Meeting, in Chicago, and most of my friends from Saint Louis were also there. Don Eldredge, a CID neurophysiologist, had attended the Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and told me, laughing: “Your ears must be ringing, everybody was talking about the Sherrick and Albernaz paper...”

Several years later, in a Collegium ORLAS Meeting, Dr. Jozef Zwislocki, an eminent audiologist, asked me how, being an otolaryngologist, I became involved in that study. “We now know,” he told me, “that this was the second paper published on central auditory masking. For a while we thought it was the first, but then we found an earlier paper published in England, one month before yours. But your paper was very important and opened a total new field in audiology.”

Sherrick Jr CE, Mangabeira-Albernaz PL. Auditory threshold shifts produced by simultaneously pulsed contralateral stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am. 1961; 33 (10): 1381-5.

Comments

Post a Comment