The Mondini Dysplasia

Carlo Mondini was an anatomist of the University of Bologna. He was born at the city of Bologna in 1729 and died in 1803.

In 1791 he made a detailed report on the dissection of the temporal bones of an 8-year-old boy whom he knew to be deaf and who had died of gangrene resulting from an infection of a foot. In fact, he had been run over by a carriage and in those days open fractures became easily infected and most severe infections were fatal.

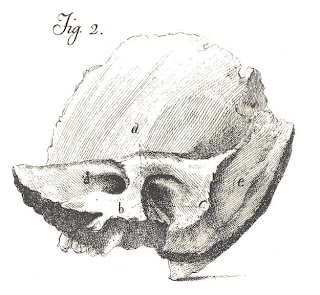

Mondini was not specialized in inner ear anatomy, so he performed his dissections very slowly, so that he would not make any mistakes. He also felt that in case he did make a mistake in the first bone, he would avoid it in the second. But he did not make any mistakes, and he himself drew pictures to show his findings. He stated that the congenital defect in this boy’s ears was the same: the superior coil of the cochlea was missing, the entire labyrinth was enlarged and the vestibular aqueducts were very large.

For many ears the Mondini dysplasia was regarded as a type of congenital hearing loss, unassociated with any type of clinical history. Many temporal bones showed the malformation, which was described histologically in great detail.

It was only in 1967 that radiologists were able to establish the diagnosis of the dysplasia in living people, so that we could learn that the hearing loss is usually assymetrical, fluctuant and progressive, and that most children with the Mondini dysplasia are born with good hearing that degenerated gradually.

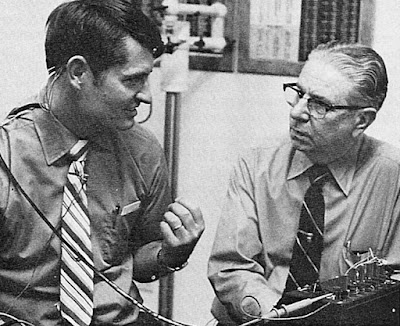

One of the histologic features of Mondini dysplasia is labyrinthine hydrops – an excessive amount of endolymph. For this reason William House suggested that and endolymphatic shunt (an operation for Menière’s disease, a disorder also with labyrinthine hydrops) might prevent further loss of hearing in children with the dysplasia. He operated many children but for some reason he never published this. We talked about it, however, and I started to work on this. My friend Fernando Chammas, a dedicated radiologist, found new positionings for the technique of polytomography of the temporal bone to render the diagnosis easier and more precise (CT scans had not been invented yet). In 1981 we published the first clinical study on the Mondini dysplasia, complementing it in 1983. We found that not only the operation reduced the progression of the deafness but also improved the responses with hearing aids. We also found that it was possible to suspect of the dysplasia by means of electrocochleography. Cochlear implants work well in Mondini’s dysplasia and are employed when the hearing loss is profound.

I was curious about Mondini’s original paper, and it happened that another friend, Mara Behlau, a speech pathologist that worked in our Department, was then in Millan, studying with Prof. Antonio R. Antonelli. When she travelled to Bologna for a meeting she went to the library of the University of Bologna and looked for the book. And she asked for a xerox copy. “Impossible,” said the librarian, “these old books suffer from the lights of the copying machines. We cannot copy them.” Mara was crying when she left the library and rejoined Prof. Antonelli. “Don’t worry,” he said when he found out what had happened. He bought some flowers for the librarian and got the copies, which she brought to me. The paper was then translated from the Latin by Prof. Leonardo Van Arcker. The pictures that you see here are drawings by Carlo Mondini, scanned from these xerox copies.

Mondini C. Anatomica surdi nati sectio. In De Bononiensi Scientiarum et Artium Instituto atque Academia Comentarii. 1791, vol VII, p 419-431. Bononia.

Mangabeira-Albernaz PL, Fukuda Y, Chammas F, Ganança MM. The Mondini Dysplasia. ORL (Basel), 1981; 41: 131-152.

Mangabeira Albernaz PL. The Mondini Dysplasia – from Early Diagnosis to Cochlear Implant. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh), 1983; 95: 627-631.

In 1791 he made a detailed report on the dissection of the temporal bones of an 8-year-old boy whom he knew to be deaf and who had died of gangrene resulting from an infection of a foot. In fact, he had been run over by a carriage and in those days open fractures became easily infected and most severe infections were fatal.

Mondini was not specialized in inner ear anatomy, so he performed his dissections very slowly, so that he would not make any mistakes. He also felt that in case he did make a mistake in the first bone, he would avoid it in the second. But he did not make any mistakes, and he himself drew pictures to show his findings. He stated that the congenital defect in this boy’s ears was the same: the superior coil of the cochlea was missing, the entire labyrinth was enlarged and the vestibular aqueducts were very large.

For many ears the Mondini dysplasia was regarded as a type of congenital hearing loss, unassociated with any type of clinical history. Many temporal bones showed the malformation, which was described histologically in great detail.

It was only in 1967 that radiologists were able to establish the diagnosis of the dysplasia in living people, so that we could learn that the hearing loss is usually assymetrical, fluctuant and progressive, and that most children with the Mondini dysplasia are born with good hearing that degenerated gradually.

One of the histologic features of Mondini dysplasia is labyrinthine hydrops – an excessive amount of endolymph. For this reason William House suggested that and endolymphatic shunt (an operation for Menière’s disease, a disorder also with labyrinthine hydrops) might prevent further loss of hearing in children with the dysplasia. He operated many children but for some reason he never published this. We talked about it, however, and I started to work on this. My friend Fernando Chammas, a dedicated radiologist, found new positionings for the technique of polytomography of the temporal bone to render the diagnosis easier and more precise (CT scans had not been invented yet). In 1981 we published the first clinical study on the Mondini dysplasia, complementing it in 1983. We found that not only the operation reduced the progression of the deafness but also improved the responses with hearing aids. We also found that it was possible to suspect of the dysplasia by means of electrocochleography. Cochlear implants work well in Mondini’s dysplasia and are employed when the hearing loss is profound.

I was curious about Mondini’s original paper, and it happened that another friend, Mara Behlau, a speech pathologist that worked in our Department, was then in Millan, studying with Prof. Antonio R. Antonelli. When she travelled to Bologna for a meeting she went to the library of the University of Bologna and looked for the book. And she asked for a xerox copy. “Impossible,” said the librarian, “these old books suffer from the lights of the copying machines. We cannot copy them.” Mara was crying when she left the library and rejoined Prof. Antonelli. “Don’t worry,” he said when he found out what had happened. He bought some flowers for the librarian and got the copies, which she brought to me. The paper was then translated from the Latin by Prof. Leonardo Van Arcker. The pictures that you see here are drawings by Carlo Mondini, scanned from these xerox copies.

Mondini C. Anatomica surdi nati sectio. In De Bononiensi Scientiarum et Artium Instituto atque Academia Comentarii. 1791, vol VII, p 419-431. Bononia.

Mangabeira-Albernaz PL, Fukuda Y, Chammas F, Ganança MM. The Mondini Dysplasia. ORL (Basel), 1981; 41: 131-152.

Mangabeira Albernaz PL. The Mondini Dysplasia – from Early Diagnosis to Cochlear Implant. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh), 1983; 95: 627-631.

Comments

Post a Comment