The Man Who Taught Me to Think

One of these days I saw a young woman who had dizzy spells and was feeling quite uncomfortable with her symptoms. In fact, the sensation of vertigo is something terrible, particularly when the first episode is intense; many patients feel that they are going to die.

But this young woman had been seen by several doctors and had been submitted to several tests. When I asked her to describe her problem she told me all about the visits to the other doctors and the medicines that had been prescribed.

“Let us start at the beginning,” I said to her, “and try to tell me what you feel when you have a spell, and how long does it last, and what you do about it. This is like a Sherlock Holmes story, you know? He always tells his clients that he must know all of the details, even those that apparently bear no relation.”

There is a serious risk that detailed clinical histories will soon become extinct. Modern medicine is too much involved with an extraordinary amount of technological progress that can be used to help us make a more precise diagnosis. But they do not replace the most important part of establishing this diagnosis, which is our THINKING. For many diseases, not only labyrinthine disorders, but many others, the medical history is the key to the diagnosis. There is no question that the many laboratory and imaging techniques available will help to confirm our thinking and establish the best treatment.

A few years ago a friend of mine, at the time the Professor of Otolaryngology of an important European University, told me that he wanted a neurosurgeon in his department and interviewed some candidates. One of them looked at a series of images and reached a diagnosis. “Let us go and examine the patient,” said my friend. “I do not need to examine the patient,” said the neurosurgeon.

This is a true story that exemplifies what I call the “mechanization of medicine.” No more patients, just file numbers. No physician-patient relationship, there is no time to establish one. We are too busy. We do not have time to loose asking questions. It is much easier and quicker to order images and laboratory procedures.

Mechanization of medicine, however, is not entirely the physician’s fault. Apparently it was the Russian revolution, in 1917, that established the principle that the governments are responsible for medical assistance to the population. The idea is noble and many other governments adopted it. And then it became too expensive. And insurance companies entered in the game. Physicians have too see more patients, because they are forced by the insurance companies to charge less than they normally would.

I always wonder why governments do not feel an obligation to supply food to the population. Hunger kills much more than diseases.

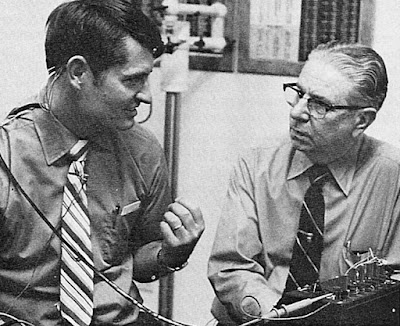

The picture that you see here is the only one that I have of Dr. José Santiago Riesco McClure, a physician from Chile who created two Neurotology Departments in the United States, one in Saint Louis and one in Chicago. His hobby was Alpinism, and this picture was taken at a mountain in Chile.

We used to see patients together in Saint Louis. He taught me to think.

But this young woman had been seen by several doctors and had been submitted to several tests. When I asked her to describe her problem she told me all about the visits to the other doctors and the medicines that had been prescribed.

“Let us start at the beginning,” I said to her, “and try to tell me what you feel when you have a spell, and how long does it last, and what you do about it. This is like a Sherlock Holmes story, you know? He always tells his clients that he must know all of the details, even those that apparently bear no relation.”

There is a serious risk that detailed clinical histories will soon become extinct. Modern medicine is too much involved with an extraordinary amount of technological progress that can be used to help us make a more precise diagnosis. But they do not replace the most important part of establishing this diagnosis, which is our THINKING. For many diseases, not only labyrinthine disorders, but many others, the medical history is the key to the diagnosis. There is no question that the many laboratory and imaging techniques available will help to confirm our thinking and establish the best treatment.

A few years ago a friend of mine, at the time the Professor of Otolaryngology of an important European University, told me that he wanted a neurosurgeon in his department and interviewed some candidates. One of them looked at a series of images and reached a diagnosis. “Let us go and examine the patient,” said my friend. “I do not need to examine the patient,” said the neurosurgeon.

This is a true story that exemplifies what I call the “mechanization of medicine.” No more patients, just file numbers. No physician-patient relationship, there is no time to establish one. We are too busy. We do not have time to loose asking questions. It is much easier and quicker to order images and laboratory procedures.

Mechanization of medicine, however, is not entirely the physician’s fault. Apparently it was the Russian revolution, in 1917, that established the principle that the governments are responsible for medical assistance to the population. The idea is noble and many other governments adopted it. And then it became too expensive. And insurance companies entered in the game. Physicians have too see more patients, because they are forced by the insurance companies to charge less than they normally would.

I always wonder why governments do not feel an obligation to supply food to the population. Hunger kills much more than diseases.

The picture that you see here is the only one that I have of Dr. José Santiago Riesco McClure, a physician from Chile who created two Neurotology Departments in the United States, one in Saint Louis and one in Chicago. His hobby was Alpinism, and this picture was taken at a mountain in Chile.

We used to see patients together in Saint Louis. He taught me to think.

Comments

Post a Comment